The Bulgarian Patent Office has adopted new Schedule of fees. The changes concern mainly the trademark fees. Now almost all...

The recent case-law from the General Court and the Court of Justice demonstrates that 3D marks that represent the shape of a product are not easily perceived as a badge of origin. They are, therefore, rarely suitable for trademark protection.

The design or the shape of a product or its packaging could be a competitive advantage. Such an important intellectual property asset can be protected as copyright, design or trademark. The various forms of protection can also co-exist, as confirmed in a recent CJEU ruling (Case C-237/19, Gömböc).

The attractiveness of the trademark protection is that it can be renewed indefinitely, it does not depend on novelty or originality and is easily enforceable. It is not difficult then to understand why so many companies go for trademark application for their product shapes.

In principle, the assessment of the distinctive character of three-dimensional marks consisting of the shape of the product itself is not different from that of other types of trade marks. It is not stricter, that is. Still, in practice it proves way more difficult to obtain registration for a shape. Only marks with shapes that depart significantly from the norms or customs of the sector are not devoid of any distinctive character.

In addition to the provision regarding the distinctive character, Regulation (EU) 2017/10001 explicitly excludes form protection marks which consist exclusively of:

- the shape, or another characteristic, which results from the nature of the goods themselves;

- the shape, or another characteristic, of goods which is necessary to obtain a technical result;

- the shape, or another characteristic, which gives substantial value to the goods;

Those grounds cannot be overcome by acquired distinctivness through use, as is the "lack of distinctiveness" ground.

The second and third provisions, technical function and the substantial value, are particularly hard to apply consistently and predictably. Therefore, each new case before the GC or CJEU is observed closely for guidance and further clarity.

Distinctive character

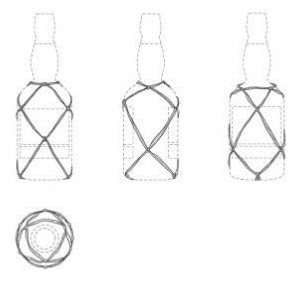

In recent judgment (T-172/19, FORME D’UN TRESSAGE SUR UNE BOUTEILLE (3D)) the GC reaffirms that in order to pass the distinctiveness bar, a 3D mark representing the shape of the product, must depart significantly from the basic shapes of the goods and not appear as a mere variant.

In its reasoning the Court states that novelty or originality are not relevant criteria for assessing the distinctive character of a trade mark. Whether the mark fulfils several fuctions (tecnical, decorative, informatiove) also has no relevance for the assessment of its distictive character.

In the particular case, the braiding on a bottle, which was applied as a trademark, does not differ substantially from that used on other bottles. Therefore, the mark will be perceived by the relevant public only as a mere decorative or aesthetic finish to the goods concerned, and not as an indication of commercial origin.

Nature of goods

The shape, or another characteristic, which results from the nature of the goods themselves, concerns signs that consist exclusively of the only natural shape of the good or its characteristic. It would apply to "natural" products that have no substitute. The example given in the guideliness of the EUIPO s that of the shape of a banana for bananas.

The same would apply to products, the shape or another characteristic of which is prescribed by legal standards. Such as a football, golf ball, etc.

Furthermore, all shapes that are inherent to the generic function or functions of such goods must, in principle, also be denied registration. So far, there are no further guidance from the CJEU about exactly when a shape is inherent to the generic function(s) of goods.

Technical function

When examining whether the mark consists exclusively of element that performs technical function, the competent authority have to identify the essential characteristics and then make the assessment of whether they are necessary to obtain the intended technical result of the actual goods concerned (T‑601/17, Rubik’s cube, confirmed by C‑936/19 P ). In doing so, it can either rely directly on the overall impression created or first examine all the components of the sign one by one. The assessment must be based on objective and reliable information, including previously granted property rights (patents, designs).

In the particular case, the overall cube shape, on the one hand, and the black lines and the little squares on each face of the cube, on the other, are necessary to obtain the intended technical result of the actual goods concerned.

In principle, the examination of the begins with the graphic representation, but when it is not sufficient, the competent authority could also refer to other useful information which would enable those characteristics to be determined correctly. The difficulty is that there is no universal approach and test that can be applied and the decision on every case is dependent on the particular circumstances.

In the case of Gömböc (Case C-237/19), the Court explains further that the examination of the functional character of the essential elements should not be limited only to the graphical representation of the mark. It can be supplemented by additional commercial information such as marketing and advertising materials.

As for the perception of the consumers of the functionality, the Court finds it relevant for establishing the essential elements and their functionality. It is, however, not to be taken into consideration when making the assessment whether the shape or its main characteristics serve purely functional role. That is to say, the perception of the public is relevant for the determination of the characteristics, but not for the application of the ground for refusal.

Substantial value

The shape, or another characteristic, which gives substantial value to the goods is aimed in particular at signs having artistic or decorative value. It refers to the likelihood that the goods will be purchased primarily because of their particular shape or another particular characteristic. However, just because a shape may be pleasing or attractive is not in itself sufficient to exclude it form registration. The concept is not to be confused with reputation, which is something that is not inherent to the shape, but is a result of the commercial activities of the trademark owner.

Uncertainties still remain in relation to a number of key aspects, including the very issue of how the assessment of aesthetic functionality is to be made.

The guidance form the case-law are that when assessing the value of the goods, account may be taken of criteria such as the nature of the category of goods concerned, the artistic value of the shape or other characteristic in question, its dissimilarity from other shapes in common use on the market concerned, a substantial price difference compared with similar goods, and the development of a promotion strategy that focuses on accentuating the aesthetic characteristics of the product in question (C-205/13, Hauck).

In the case of Gömböc (Case C-237/19), mentioned above, the Hungarian Office had found that the shape embodies an attractive and striking design. Furthermore, it was filed for decorative objects in classes 14 and 21. Those findings, however, were not sufficient to conclude that the mark represents the shape, which gives substantial value to the goods. The CJEU ruled that the competent office still must examine whether, in the specific case, the conditions for applying the ground for refusal are met, namely whether the sign applied for consists exclusively of the shape which gives substantial value to the goods.

In conclusion

Obtaining trademark protection for the shape of the goods has imortant legal and economic benefits for the trademark owner. Therefore, we should not expect such application to decrease. However, the lack of clarity of the grounds for refusal, especially regarding the technical and aesthetic function, leaves room for doubt as to the strength and scope of protection of such trademarks. Hopefully, the Court will be consistent in its practice and would provide further guidance and clarification.

The article is for information purposes only. It should not be considered as replacing advice from an IP expert. TULIP would gladely assist, should you need consultation regarding trademark protection for the shape of products.

*Attribution: the image is By Kicsinyul - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=65197278